Part 2: Pre-Production – Writing That Blockbuster Screenplay

There are three basic parts of filmmaking:

- Pre-Production

- Production

- Post-Production

Pre-production involves getting the storyline together and creating a screenplay.

A screenplay is about 120 pages long and involves scenes and dialogue. However, this page length varies by genre. For comedy scripts (i.e. romantic comedies), you can get away with 90-100 pages. A lot of horror scripts, especially contained horror scripts, can be 80-90 pages.

Most drama, action and thrillers often exceed a 100 pages and are closer to the traditional rule of 120 pages.

Some writers like Aaron Sorkin are quite verbose. “Social Network” is at 163 pages!

As an indie filmmaker, we often prefer to work with screenplays around the 90 pages. Every page counts as a minute of film footage. This in turn helps you estimate the cost of producing that screenplay. Keep this rule (1 minute = 1 page) in mind as a film producer. For screenwriters, this is a good rule of thumb when estimating screen time for your spec scripts.

A screenplay is really just a draft of the film. The director will take charge as to which angle to shoot scenes. The actors will make their parts come alive. Some actors will want more control over their characters. The director will also fight for control.

Even if you are doing this on the fly and are hiring your best friends to do this job and make your own movie, expect a battle of control. Whenever you work with creative people, understand that they have egos.

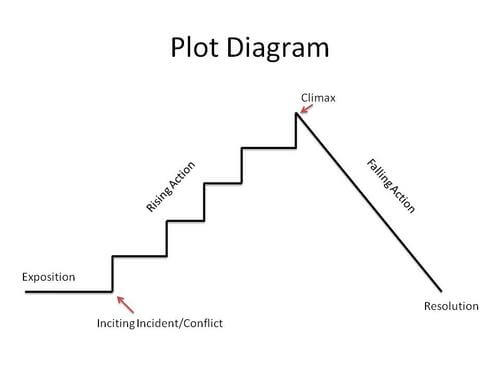

Your movie should have a point and tell a story. Just like a book or any other written entertainment, you have to have the following in order for your story to work:

YOU HAVE TO PRESENT A CONFLICT AND SOLVE THE CONFLICT IN THE SCREENPLAY.

You can read all the books and listen to all the screenwriting gurus in the world. You can forget everything, but always remember this one simple rule of creating conflict.

Here is a clip from Wall-E’s typical day at work. In a little over a minute. It’s jam-packed with conflict. Without knowing about Wall-E, you learn that his job is to clean up the mess in a city.

The conflict in this short clip is both internal and external. The external conflict is the fact that Wall-E has to clean up this huge city and it’s just him.

The internal conflict is Wall-E’s search for meaning and self-actualization. This is hinted at as he rummages through the garbage in search of interesting mementos to take back to his home.

Pixar scripts are great starting places to learn script writing. In this short clip, you can get a feel for Wall-E, his world and the challenges of his current situation. And the amazing part? The clip used no dialogue! It’s purely visual, yet so powerful.

Your main goal as a film producer or as a script writer is to entertain. I wish we all had access to Pixar scripts. Regardless, your main role as a filmmaker is to find a compelling script that will keep an audience’s attention.

This means creating conflict and tension in every bit of dialogue, every mise-en-scène, and every cut.

There are some people that refuse to understand this basic concept of fiction and even non fiction writing.

You introduce your characters, you present a problem that they have, you work towards solving the problem, you have a climax to the film in which the problem is addressed and an ending in which everything is resolved. It doesn’t have to be resolved “happily ever after” but it has to be resolved.

You cannot leave the audience thinking that they didn’t get a conclusion to the problem. Even if it is one they don’t like.

When you write a screenplay, it doesn’t usually pop out of your head the way the final product reads. This is true whenever you write a book or even an article. There are usually rewrites required.

You may have to rewrite your screenplay several times before you get it right. Then, if you are fortunate enough to sell the idea to a producer, they will rewrite the entire thing.

The screenplay should introduce all of the characters through dialogue and also introduce the setting of the movie. Writing a screenplay is no different than writing a play. It is just different because of the technical aspect of filming on the screen.

Instead of directions like “stage left” you will most likely put “fade to black” in your screenplay, but for now, when you are starting out, the main objective is to get your idea down on paper.

Try to make your screenplay original and something that hasn’t been done before. You can work on the screenplay with a trusted friend, aka Ben Affleck and Matt Damon on “Good Will Hunting.” You may even, like Affleck and Damon, who wrote this Academy Award winning film out of college, become famous and get to start dating people like Jennifer Lopez.

There are three basic ways you can write a screenplay:

- Linear: Story moves from beginning to end

- Non-Linear: Movie jumps around in sequence

- Documentary: Interviews and anecdotes break up narrative sequences (or mockumentary):

There is an old saying that when you are writing a book or a screenplay, start in the middle. You are better off to pack a punch in the beginning of your screenplay and get the audience interested in the characters right away rather than start from the beginning to the end.

Screenplay Summary of Citizen Kane

While most films are made in the linear fashion, the more effective films are made in non-linear mode. One of the greatest films of all time is considered to be “Citizen Kane.”

Take a look at the film and see how the screenplay flows. It begins with the death of Kane and then takes us back to his childhood. We then skip around to the people who knew Kane and their recollection of this man. Most of the story takes place in flashback sequences.

The meaning to the elusive “rosebud,” the dying words of Kane, brilliantly played by Orson Wells, is not discovered until the end of the film and in a very poignant matter. And it alludes to something that is seen early in the film but not given any significance. When you see the ending of this movie, it packs quite a punch and you certainly understand the life of Charles Foster Kane.

Citizen Kane combines documentary, linear and non-linear style. It presents a conflict early in the story and solves the conflict at the end. In the meantime, it tells the story of a remarkable man, reputed to be modeled after William Randolph Hearst.

Other Great Examples of Compelling Scripts

Using flashbacks are a good way to tell a story and are used in today’s films as well as classic films. “Casablanca” tells the story in a linear fashion but also relies on flashbacks to France when the star crossed lovers, played by Ingrid Bergman and Humphrey Bogart, were together.

Flashbacks can give the audience bits of the story that are left out if it is told in linear fashion.

“Pulp Fiction” is a good example of how a story is told in non-linear fashion, but in which all of the sequences of the film come together brilliantly at the end and tie into one another.

Pulp Fiction, a film by Quentin Tarrantino, appears to be several vignettes of separate story lines that all relate to one another. It is a clever and entertaining way to tell as story.

When you create the storyline, you want the audience to be delighted at the end or shocked. But you want them satisfied. Think of the film “Shawshank Redemption.”

This is probably one of the best films made recently and based on a short story by Stephen King. It is told in linear fashion, but then takes you through a series of flashbacks at the end.

The purpose of this book is not to give away the ending of this film which is definitely worth watching if you are interested in screenwriting and producing your own film.

The one thing that you do not want to do is to not resolve the conflict. Yes, we can cite the ending of pictures like “The Blob” where a question mark is placed after “The End” but there is still a resolution to the conflict.

The blob is captured and sent to the North Pole. There is a happy ending for the major characters of the story line who were trapped in a diner by the blob. Had the story ended with the blob killing everyone in the diner and then just continuing to grow, it would not have been a successful “B” movie and would not have launched the career of Steve McQueen.

You have to have resolution of the conflict that you created by the end of the film. It is also good to make some sort of point with your film. You should think of your screenplay as telling a story with film instead of writing it as a book.

The purpose of telling a story should be to get an idea across. Just like the purpose of this book is to hopefully teach you something about making your own movie, you should have a reason why you are making your movie.

Your point can be subtle or it can be a hit you over the head with a hammer point like Michael Moore, who has been very successful in making documentaries that are entertaining as well as revealing. While some may argue with Moore’s politics, no one can argue with his film making abilities. His films will capture your attention from the beginning to the end and all make a point.

Once you have your story, you can write it in the form of a screenplay. The screenplay is mostly dialogue that tells the story from the viewpoint of the characters or, in the case of a documentary, from the narrator.

You can also use narration as a way to fill in bits of the story line not discussed by the characters or revealed in the film. This is often known as voiceover and is used very successfully in the film “Goodfellas.”

You want to narrate less in screenwriting and use dialogue more. The old “show me and don’t tell me” applies to screenwriting more than any other type of writing.

Your characters should be demonstrating the flaws and strengths of their personalities through their dialogue and how the film moves along. This is the same as if you are writing a book or a short story. It is more effective if you show that Mary is selfish by some of her actions rather than just saying “Mary is selfish.”

Common Screenwriting Mistakes to Avoid

As a story analyst as well as a filmmaker, I covered more than my share of bad scripts, and most of them were bad for all the same reasons. We’re not talking about improper formatting or typos (although I saw plenty of both), but rather, the same fundamental story errors that kept otherwise good writers from moving on to the next level. Here is a list of common mistakes that separate the professional screenwriter from the amateur.

Nothing to Lose

In most scripts that receive a pass, the hero is not risking anything. The audience must know what the costs the hero is willing to endure to do the right thing – and whatever they are, they must be valuable to the hero. This holds true for all the characters in the script, but especially the protagonist.

Clichéd Characters

This is another one of those seemingly contradictory rules in screenwriting. The characters must be familiar, but they must not be too familiar. It’s up to you as the screenwriter to give your familiar characters some sort of twist. Familiar character types provide a base for you to sculpt a unique character. Without the base, the character falls down. The twist also provides an unexpected surprise, leaving the audience thinking – ‘hmm… I thought I knew this person. Isn’t that interesting.’

Dramatic Tension

Most screenwriters realize the need for conflict, but what separates the pros from the rest of the pack is the concept of building tension. As we move through the screenplay the stakes must get higher and higher, until ultimately the hero’s core values are at stake. Don’t think that putting the main character’s life on the line is necessarily the ultimate stake. If we don’t care about the main character, or if we think the main character is willing to die for any cause – this stake is effectively rendered useless.

Enough With Stage Direction

Many screenplays simply have too much stage direction. Only include what is relevant to the story. Set the scene. Set the characters within the scene. And pretty much that’s it. Most readers, although they won’t admit it, gloss over the stage directions anyway. This may seem to contradict the idea of visual storytelling, but it doesn’t really. The reason most readers gloss over stage directions is that 99% of the time, they are meaningless.

Also remember that stage directions are what we see. Try not to include things we cannot see. You can get away with it occasionally – when setting a mood for example, but for the most part, just concentrate on the bare visuals necessary to move the story forward.

Sinking Subplots

In an amateur script, the subplots usually don’t reflect the main plot. In these cases, the subplots are actually pulling your reader out of your story. They are a different story altogether. Because screenplays are so Spartan, you cannot afford to devote screentime to plot elements that don’t more the main story forward. This is not a luxury you can afford.

Closely related to this are setups that don’t have payoffs. If you set up a plot point, you have to pay it off. Otherwise, why include the set up? You could say it’s a red herring, but even a red herring must have a payoff – just one that is unexpected.

Deus Ex Machina

Okay – I know this is one of those writery terms that just sounds cool – but don’t do it. Don’t even come close. They undermine the hero and thus your story.

The Other White Meat

Think of the villain as the other side of the hero. Without a villain, the hero is incomplete. Often in amateur scripts, villains don’t have a lot to do. They are a vague threat. They show up every so often, but almost all the screentime is devoted to the hero. We need to see the villain in action to know why the hero must defeat him. Just remember to construct your villain as the dark side of the hero. Then when you are writing the villain’s scenes, in effect you are writing the hero’s scenes.

No Opposition

If a candidate for elected office is running without opposition, would you watch the election results? Obviously not – there would be no point. The same holds true for your stories. If the hero has no real opposition or is never in any genuine peril, there’s no point in watching.

The bottom line is to examine your script for any of these potential pitfalls and fix them before you submit the script. Always remember there are no steadfast rules. There are, however, overriding tendencies that will help improve your chances of success.

The Screenwriting Grind

The most difficult part of screenwriting is the grind- actually sitting down and finishing the script.

Assuming that you want to write a script or story for your movie on your own, the actual writing can be difficult to find motivation for. Instead of discussing screenwriting itself (which another part will cover), this article intends to get your butt physically into a seat and start writing. First off, you have to acknowledge where exactly you are starting from. Do you have only the vaguest idea of what you want to write about?

Did you already write an outline plotting out the major story turns? Or maybe you have the entire story envisioned in your head but you are not entirely certain how to translate it to paper. Which of these best describes your current situation? While it may seem like a disadvantage if you are not as well equipped in the pre-writing department, do not be discouraged; there is no correct way of writing. The only thing that matters is ending up with a finished product of quality. The means by which you achieve this is up to you.

There are several details that a writer should consider before setting up his/her work environment. If noise distracts you, set up in a place that is far away from daily commotion. Many people are continually distracted by television or the internet so, if you are one of these people, either unplug everything or get to a room with no media diversions.

Background music can often help maintain a certain mood that you want for a story and possibly inspire you (Paul Thomas Anderson says Magnolia was partly a result of listening to Aimee Mann’s music while writing). Just as many writers enjoy only the sound inside their heads to accompany their process.

Once you have found a location that matches your needs, it is time to sit down and stop making excuses. As you begin to be distracted, your mind will come up with small reasons on why you should temporarily discontinue. The ‘temporary’ part was conjured up as lame justification. It is half of the writer’s job to refuse any temptation that brings them away from their work and they can do this by heading off any distractions.

If you eat your meals immediately before you sit down, you no longer have the hunger excuse. The phone may become your worst enemy, so you may want to turn it off until you have accomplished a substantial amount. While you are closing yourself off to the world for a few hours, I guarantee you that not much in the outside will have changed (and even the parts that did change can probably wait).

Of all the excuses that the tired mind devises, writer’s block is the deadliest. After writing for half the amount of time you intended to, you may say to yourself, “Writer’s block is taking over, better take a break until tomorrow.” Be strong against this feeling. Writer’s block is merely a fancy way of saying, “I don’t know exactly where the story goes from here and I’m afraid to make a commitment just yet.”

Instead of being afraid, take the opportunity to follow a brief impulse of taking the story into a different direction. At the very worst, the new direction might not work, at which point you erase it; the point is that you continued writing and spent the extra hour defining what your character/story is and is not. At the very best, you find yourself writing a much better story because you were unafraid of hunting for it.

Another form of writer’s block may leave you with the feeling that you absolutely cannot go on. Every word you write feels shallow and contrived. The dark side of your mind pushes you toward taking a break, but which is better: writing something crappy while exercising your writing muscles or simply not writing at all? If you absolutely must get up and walk around, always keep your head on your characters. Put them through different scenarios and imagine five different directions the story could go. Your story has to become part of your life. The more it remains in your mind, the more it will flesh out into exactly what you want.

“Inspiration cannot be forced,” some writers may say.

This is true, but it does not give you the excuse to watch television endlessly until something hits you. An hour spent writing is always much better than an hour wasting time while you are waiting for inspiration. Shower Ideas (the ones that come to you suddenly while you are bathing) can be saved for the next draft of the story. Those ideas are always miraculous and must be followed, but at the same token you cannot stand in the shower waiting for them while your fingers start pruning.

The key to writing is gaining experience. The way you can gain the most experience is to challenge yourself to work onward even when times are rough. If you are able to keep your head on your story and avoid all distractions, you have a much better chance for success. Always remember that you can find your story as long as you are willing to chase after it.

Conclusion

The most important part (yet the hardest) is putting your vision to paper. Many industry experts agree that the screenplay is the backbone of making a movie so it’s best to get this step correct. If you create compelling characters, you’ll attract the best actors as they’re always looking for the next great challenge. Create compelling scenes and you’ll give your director of photography lots of ideas to shoot stunning footage with his or her cinema camera. Create a compelling world and your audience will keep coming back again and again to see your movie.

Many auteurs, like Woody Allen and Quentin Tarantino, are great directors as well as screenwriters. They understand and appreciate that a great movie starts with a great script. So create a compelling screenplay and it will set the tone for the rest of your movie.

2Bridges Productions Copyright © 2017. Address: 25 Monroe St, New York, NY 10002. Phone: 516-659-7074 – All Rights Reserved.

We are a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for us to earn fees by linking to Amazon.com and affiliated sites.