Screenwriting Tips: Proper Screenplay Format

First, all of the formatting I talk about herein cannot be duplicated in the Associated Content text editor, so pay close attention to this How-To advice so you can properly format your screenplay and make your movie.

This How-To is designed to help readers and first time screenwriters format a screenplay who do not have access to screenwriting software such as Final Draft or Movie Magic Screenwriter.

The mentioned software is highly recommended (I use both of them) but if you simply cannot get your hands on it for one reason or another it is important to know how to properly format a screenplay. Additionally, Microsoft Word or another word processor can be used for screenwriting.

If you’re serious about screenwriting, in addition to reading this How-To, I recommend strongly reading any and all screenplays you can get your hands on as well as picking up

“Story: Substance, Structure, Style and the Principles of Screenwriting” by author Robert McKee.

Mr. McKee has been in the biz for years, he knows his stuff. The book is truly fantastic and extremely informative, and best of all affordable. It will not only show you the basics of proper screenplay formatting, but also show you how to structure a story.

Also, it should be noted that if you choose to read screenplays from movies that have been produced already, keep in mind the screenplay you are reading is most likely a “Shooting Script.”

This means it has been messed with by the studios and includes aspects and elements that are not added until after the screenplay is sold/produced (essentially, it’s the blue print for shooting the movie, hence the name). For example, a lot of transitions (DISSOLVE TO: CUT TO: etc.) are not a part of a “Spec Script,” which is what you are writing initially. Basically what I’m saying is there’s more work done to a Shooting Script than is necessary for a Spec Script.

Proper Screenplay Length

“Feature-length” seems to be a gray area.

The Academy, yeah those guys who put on the Oscars every year, classify a feature-length screenplay as anything over forty (40) pages. Now, in the real world, where most of us live, feature-length is considered at least ninety (90) pages, but depending on the genre you’re writing in, the screenplay could be anywhere from ninety (90) to one hundred and twenty (120) pages.

A helpful hint: write as long a screenplay as you want, but if you’re going to send it out to a studio script reader, trim the screenplay down to no more than one hundred and twenty eight (128) pages.

Why? One page of a screenplay equals about one minute of screen time; one hundred and twenty eight (128) pages is equal to a two hour and eight minute (2 hrs 8 min) movie and anything over this threshold has been deemed “too long.”

With all of that out of the way, let’s get started. In the following I will break down each element of a screenplay and it explain it in a way which, hopefully, can be understood.

As a note, everything that is in ALL CAPS is intentional, when you write a screenplay the elements that appear within in ALL CAPS should also be written in ALL CAPS in your work, also take note of the punctuation following the ALL CAPS.

Transitions in a Properly Formatted Screenplay

Transitions are always aligned to the right side of the page and are used to move from one scene to the next. Transitions are an element which are added to Shooting Scripts with a few notable exceptions.

The exceptions are, FADE IN: FADE OUT. and FADE TO BLACK. Everything else can be ignored, but for the sake of this How-To I’ll explain what each Transition means and the role it plays.

BACK TO: When you have cut from one scene to another and are going back to the original scene. For example, you go from a restaurant to a house and want to go back to the restaurant to finish the scene. As I stated, this can be ignored unless you’ve got a damn good reason for it to be included.

CUT TO: Similar to the BACK TO: transition, this staples the end of one scene and the beginning of the next together. For example, the scene at the restaurant has ended and you CUT TO: the scene in the house.

Other variations include MATCH CUT, which matches the object in one frame with the next frame. This is a great example:

Finally, there is the SMASH CUT, which is really just a fancy CUT TO. It is designed to be jarring to the viewer. A great example can be found in “Vanilla Sky:”

DISSOLVE TO: When the end of one scene overlaps with the beginning of another.

FADE IN: You must use this transition at least once in your screenplay. Where must you use it? The very beginning. Before you type a single word of your story, you must type FADE IN: Other than that, don’t worry too much.

FADE OUT. Just as FADE IN: begins your screenplay, FADE OUT. ends the screenplay. This transition is interchangeable with FADE TO BLACK. It does not matter which one you use as long as you use one of them at the very end.

FADE TO BLACK. Just as FADE IN: begins your screenplay, FADE TO BLACK. ends the screenplay. This transition is interchangeable with FADE OUT. It does not matter which one you use as long as you use one of them at the very end.

FADE TO: Similar to DISSOLVE TO: the FADE TO: transition fades out at the end of one scene and fades in at the beginning of the next. Again, don’t use it unless you’ve got a true artistic purpose behind doing so.

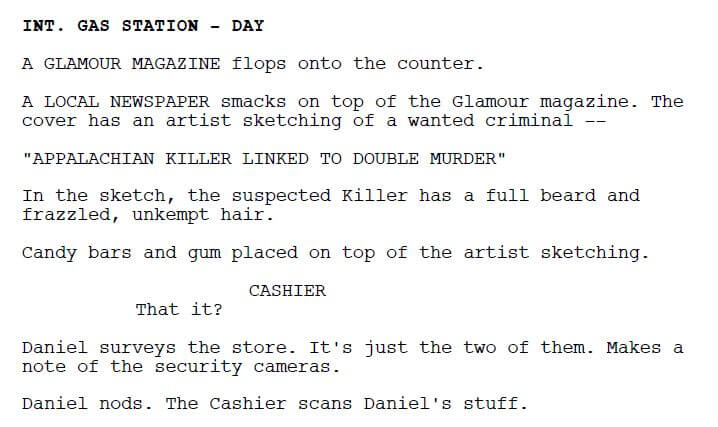

Locations and Scene Heading

A location or scene heading is made up of three parts:

- Inside (INT.) or outside (EXT.)

- The Specific location (i.e., Cafe)

- Time (Day or Night)

So if I wanted a scene inside a bathroom during the day it would appear as such:

INT. BATHROOM – DAY

And if I wanted a scene outside of a house at night the heading would appear as such:

EXT. HOUSE – NIGHT

What if I wanted a scene both outside and inside? Easy. Use the location I/E. INT. for interior, EXT. for exterior and I/E. for interior/exterior. This location is used a lot for scenes in a car. Example, I/E. CAR – DAY

What if you have a scene that starts inside and ends outside? Simple, you just create a new scene heading and continue the scene. Every scene must start with a scene heading.

With the time of day, you can get creative if you want. For example writing AFTERNOON instead of DAY. If you want to, you can. I personally do not because I believe it’s a decision best left up to the people involved in the production of the movie so I stick to DAY and NIGHT.

ACTION

Action follows the scene heading. The action is what is going on in the scene; what the characters are doing and what we, the audience, see. Adam walks to the faucet, Adam karate chops his dog, blah blah blah. The action and scene heading should appear with a space between the two, like this.

INT. HOUSE – DAY

Adam walks to the faucet and pours himself a glass of water.

…Make sense? Okay, on we go. Also, action is aligned to the left under the scene heading as you can see. Action takes place in present time, as we are seeing it happen. Because of this fact you must write in the present tense.

So what does this mean?

Here’s an example: Adam walks is the correct way to write action, not walked or walking. Keep everything in the present tense, it’s a little difficult to get used to at first, but you’ll get it with practice.

With action, you can be as descriptive or non-descriptive as you like. Talk about the scenery and what’s going on in the background if you wish, but do not let it draw the readers attention away from the characters and the story. It should also be noted that the very first time you introduce your character or any character their name must appear in ALL CAPS. For example.

INT. HOUSE – DAY

Keys jingle on the other side of the door. They can be heard as they are inserted into the lock. The knob turns and door swings open, ADAM (late-teens) enters the house and drops a bag of movies to the floor.

…This is how we introduce our character Adam for the first time, after this we can write his name as normal. Also note how I clarified his age. Again, you can be as descriptive or as non-descriptive as you like with your character. Make him black, white, Asian, fat, skinny whatever you want.

When you use the word “camera” it will also appear in ALL CAPS, as will its movements.

Example: the CAMERA PANS across the desert.

This is another shakey area. I don’t use the word camera because I feel it takes away from the story and I don’t know what the camera should do, I’m not a director. Leave the camera work to the professionals.

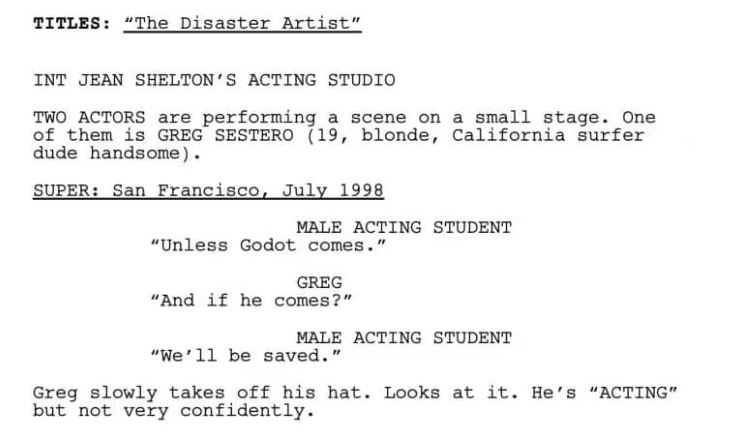

If you want words to appear on the screen such as “Denver, Colorado” you would indicate this with something called a SUPER. SUPER is short for superimposed.

It appears as action, aligned to the left, on its own line and in ALL CAPS. It can also be underlined to call it out.

SUPER: Denver, Colorado

Just like this on the script “Disaster Artist” —

Character

Characters names, when they speak, are always in ALL CAPS and their name should be in the center of the page.

ADAM

I’m Adam and my name is

centered in all caps every time

I speak.

Dialogue

Dialogue, should appear centered under the character’s name. If you use screenwriting software your dialogue will appear tight, as it does above, otherwise you’ll have to adjust it manually, or just keep it centered under the name.

Dialogue can be anything you want. If you want your characters to talk about coffee and cigarettes, let them go nuts. Quentin Tarantino said in an interview with Charlie Rose “I push the characters in a direction, but if they want to talk about something else while they go from point A to point B, I let them.”

I’m paraphrasing, of course, that is not a verbatim quote. His point is, let the characters be who they are, let them tell you what they want to talk about. If the dialogue moves the story forward and/or reveals something about the person speaking, then it’s all good.

Extensions

Occasionally when you read a screenplay you will see something referred to as an “Extension” after the name of a character speaking.

These extensions help clarify where the character is placed in the scene if they cannot be seen; occasionally extensions indicate if something the character said needs subtitles.

Here are all the extensions you will see, similar to transitions, not all of them are used. An extension looks like this ADAM (V.O.) the paranthesis are the extension.

(O.S.) This extension stands for “Off Screen.” Off Screen means we can hear the person speaking but cannot see them. It’s probable the speaker is nearby.

For example, when someone is speaking to another person through a door you would use the (O.S.) extension for the person you cannot see. (O.S.) is to be used for writing a film screenplay, which is different than (O.C.) When writing a movie, never use (O.C.)

(O.C.) O.C. stands for “Off Camera,” which is different than Off Screen. Off Camera means the person we cannot see is in the same room as another character he/she is speaking with but cannot be seen because maybe the camera is trained on only one person.

So if Adam is at a table and the director has the camera at a close up on Adam, Adam will fill the screen. We can’t see anyone else. So if Stacey is at the other end of the table carrying on a conversation with Adam, all of her dialogue would be labeled as (O.C.) until she was brought into the shot, that is to say, appears on screen.

It’s important to remember that if you are writing a movie script you do not use (O.C.), you will use (O.S.) you will use (O.C.) when you are writing for television. (O.S.) = film (O.C.) = TV.

(V.O.) This stands for “Voice Over” which means we can hear the person speaking but they are not nearby and not on screen. Voice Over is used mainly for narration. Also, use this when someone is speaking to a person on the phone.

If the shot is cut back and forth between the two talking (meaning you see both people) on the phone you wouldn’t use (V.O). If you see only Adam on the phone, but here Stacey’s voice, all her dialogue would appear as a (V.O.)

(SUBTITLE) Subtitles are used to indicate the person will be speaking in another language. If Adam speaks Japanese but you, the writer, don’t know Japanese you would write the dialogue in English and indicated with (SUBTITLE) that the actor is speaking in another language.

(CONT’D) This extension stands for CONTINUED. If you have a character speak, then have him perform an action and then speak again, his dialogue will be CONTINUED, which is short for CONTINUED FROM ABOVE. Unless you have a screenwriting software which inputs (CONT’D) automatically, do not worry about putting it in, everyone can see the character has resumed speaking.

Parenthetical

The parenthetical, informally known as the “wryly” is a useful, but overused tool. Parentheticals appear under the character’s name who is currently speaking and they are used to provide extra information for the reader or actor on how to speak the following lines.

If you want the actor to speak the words angrily or sarcastically you would indicate as such in parenthesis under the character’s name. You can always use these to indicate if the character is speaking another language.

ADAM

(in Japanese)

Thank you.

The words in parenthesis, “in Japanese” are the Parenthetical. They are used in this manner to indicate Adam is speaking in Japanese, but the dialogue is in English because we’ve attached the “Subtitle” extension, as explained above.

As a side note, If you know Japanese, or another language and want to type certain parts of the dialogue in that language, by all means go nuts. If you’re character speaks Japanese and you don’t necessarily want the words subtitled, you just type the dialogue as you would if you were typing in English.

ADAM

Arigato.

See? Easy as…something that’s easy.

Shots

Shots are another unused part of “Spec Script” screenwriting. They are used to indicate camera movements, angles etc. Unless you’re directing the movie yourself and know what to put in and how to correctly use Shots, don’t bother messing with them, it can get messy.

But for the sake of the How-To, here are the common Shots you will run across. They appear aligned to the left and are in ALL CAPS.

FROM THE TOP DOWN – When you’re shooting from a high point to a low point, like from the top of house to the ground where the action is happening.

CLOSE UP or CU – This indicates the camera will be really tight and close on a person, used for facial expressions.

WIDE – When you want to capture a wide array, maybe two characters are at opposite ends of a football field and you want them both in the same shot.

ANGLE ON – During conversation, you would indicate who the camera is pointed at, usually the person speaking.

Summary of Script Formating

Writing the script is an important part of pre-production. In essence, without a solid script, there is no movie! It’s important to understand the basics of proper screenwriting format so everyone on the set from the producer to the PA can understand the story.

You’ll soon learn that all these rules are not set in stone. You’ll ignore some rules; some you’ll never break. As you craft and discover your own style, you’ll learn what feels right to your style of screenwriting.

For now, as a beginner, stick to the rules of proper screenplay formatting and you’ll be on your way to writing that next Hollywood blockbuster.

2Bridges Productions Copyright © 2017. Address: 25 Monroe St, New York, NY 10002. Phone: 516-659-7074 – All Rights Reserved.

We are a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for us to earn fees by linking to Amazon.com and affiliated sites.